On Sunday, December 14th JCVI scientists Andy Allen, Erin Bertrand, and Jeff Hoffman flew to New Zealand to begin the arduous journey to the sea ice edge of Antarctica. The JCVI team was joined by three members of the University of Southern California, led by David Hutchins, and three members of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), led by Deborah Bronk. This is the second field season of the second three-year NSF funded collaborative project for the Allen team. The first field season for the current project was in December 2012/January 2013; the second year was postponed due to the government shutdown in late 2013 delaying our trip until December 2014. The major objectives of this collective fieldwork are to understand how changes in micronutrient availability, temperature, and pCO2 will impact growth, community composition, and nutrient utilization in Southern Ocean phytoplankton.

Pictures from Antarctic Expedition

Pictures from Antarctic Expedition

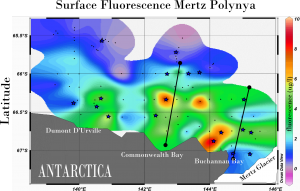

Antarctica and the Southern Ocean remain one of the most untouched regions on the planet making this area extremely valuable for research related to the impacts of climate change on biota. The Southern Ocean is a system of currents linking all of the Earth’s ocean. It is the most prolific of our oceans, and by conducting genome-enabled investigations targeting phytoplankton, plant like organisms consisting mostly of algae and bacteria that are the base of oceanic food webs, JCVI scientists glean insight into key biological underpinnings. A key research challenge is identification of basic characteristics, features and genomic fingerprints that are sensitive to environmental shifts that impact surface waters and result in nutrient cascading effects. JCVI scientists are establishing valuable baselines to identify impacts of climate change on ocean ecosystems. This research is used in turn to create models of ocean circulation and phytoplankton distribution patterns that will help scientists, policy makers and politicians identify and address the worldwide effects of climate change.

This research can be especially challenging because of the geographic isolation of the Southern Ocean. Upon arrival in New Zealand, the JCVI team spends a day securing extreme cold weather gear and viewing safety videos. We then wait patiently to depart on a military plane: LC-130 Hercules. While the LC-130 is known for its reliability to reach austere locations, the flight is often at the mercy of mechanical failure and weather changes. After a nine hour, extremely loud and rumbling flight, the team disembarks onto a sheet of ice. Despite this being a repeat trip for many of us, it is still amazing to find yourself traversing a remote sheet of ice. From here, we board the transport vehicle Ivan the Terra Bus for the 45-minute ride to McMurdo Station on Ross Island.

Orientation to station life can be challenging. There are acronyms for everything. Despite the presence of approximately 1000 residents, one is aware of the lack of “home like” sounds from pets and children, and the feelings of isolation are real and enduring. Interestingly less than 10% of the Station population is scientists. We work with military and station support staff daily, and despite the isolation, a sense of camaraderie and a bond based on shared experience develops immediately. Another note of interest is that the weather at times is not that bad at McMurdo despite what you may have seen in the movies. In fact, our friends and family in Boston had it much worse!

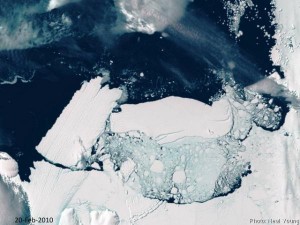

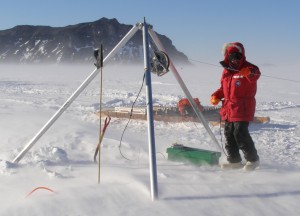

After arriving at McMurdo, the team spent 9 days completing required safety training, securing logistical support and preparing the lab. Our research activities consisted of weekly helicopter expeditions to the sea ice edge where large volumes of water were filtered for analyses of DNA, RNA and proteins. Live phytoplankton samples were also collected in a manner specifically designed to prevent contamination by iron and other trace metals. There are inherent dangers traveling to the sea ice edge. In the company of penguins and whales, the team must be aware of potential ice shifts, developing cracks and breakouts. We travel with a mountaineer who works to maintain our safety. When working close to the ice edge, we are each secured via ropes and pulleys—it can be intense. We also have to watch the weather. Many times in order to keep samples from freezing, you could see us breaking out the hairdryers and camping stoves. Whatever it takes!

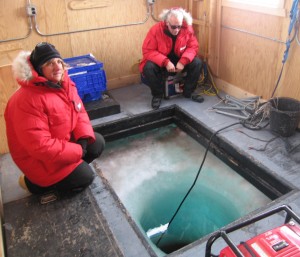

Our “live water” samples were transported back to the laboratory at McMurdo and used to conduct various manipulative experiments aimed at investigating the synergistic impact of change in Iron (Fe) and Vitamin B12 availability as well as increases in temperature and pCO2 levels. One of the major challenges the team faced was keeping these experiments free of dust in order to avoid iron contamination. This was a particular challenge because McMurdo Station is built on a pile of extremely dry, dusty, volcanic soil. The team persevered, of course, and completed numerous trace metal clean experiments.

To date, these manipulative experiments have yielded preliminary results suggesting that changing micronutrient availability and increasing temperature will have major impacts on the base of the Antarctic food web. These include changes in mutualistic relationships between phytoplankton and bacteria and changes in the rate of consumption in major nutrients, both of which are likely to have important downstream effects throughout the global ocean. Analyses of gene and protein expression changes in the field and in these experiments are just beginning to yield further insight into how the Southern Ocean will respond to a changing earth.

On January 27th, exhausted, but with a very successful expedition completed, the team returned to New Zealand. It is challenging to be away from your friends and family for 2 months at time. As we return to the real world though, we arrive feeling lucky and privileged. JCVI scientists see a region of the world and experience amazing days of wildlife that few people will ever know first-hand. Studying phytoplankton and ocean ecosystems is in fact a privilege and the research JCVI scientists and other teams are doing in Antarctica will have a lasting impact on the future of our planet.