New Individual Human Diploid Genome

The first publication of a diploid human genome from one person: A step closer to truly individualized genomic medicine

In 2001, two versions of the human genome were published enabling researchers a first look at humans at our most basic level. While these achievements marked a new era in science, it was clear that more analysis and more sequenced genomes were needed for a more complete understanding of human biology. And because these first published genomes were mosaics of many people's genomes, rather than genomes of individuals, it was likely that much of the key information about each person — what particular traits or propensity for disease were coded for in their genes, was missing. In short, the era of true individualized genome medicine was not yet realized, until now.

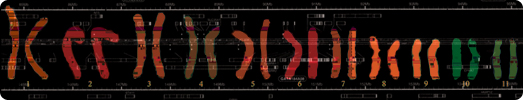

Today, researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute, along with collaborators from Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, the University of California, San Diego, and the Universidad de Barcelona in Spain have published the first diploid genome of an individual — Dr. Venter, in PLoS Biology. This analysis and assembly of the 20 billion base pairs of Dr. Venter's DNA is the first look at both sets of an individual's chromosomes (one inherited from each of his parents) and has shown a greater degree and more kinds of genetic variation with human to human variation five to seven times greater than in previous genome analysis. All the data for the first human diploid genome has been deposited at NCBI, and JCVI researchers have also developed a new genome browser that highlights the newly discovered variation.

This new individual genome has tantalizing vistas — more than 4.1 million genetic variants covering 12.3 million base pairs of DNA. More than 3.2 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 1.2 million never before seen variants and nearly a million non-SNP variants. But it's still only the beginning. Many more individual human genomes need to be sequenced, the technology to do so needs to improve, and additional analysis of this first reference human genome will continue. Researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute are forging ahead on all these fronts in their quest for new and better understanding of human genomics.